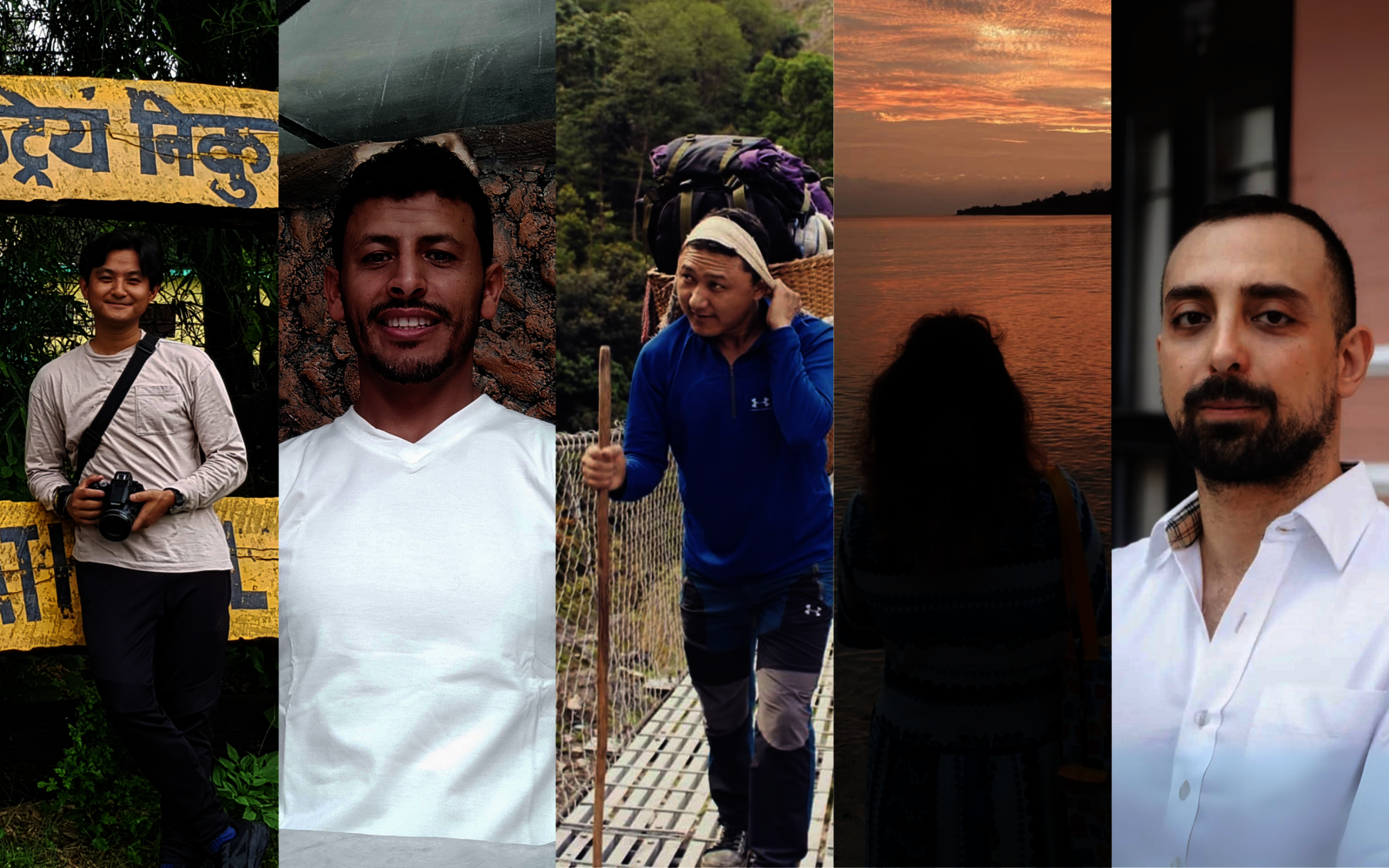

Since the US government withdrew its global humanitarian funding in January, aid workers around the world have been losing their jobs, a catastrophe both at home and in the communities they serve. Five of those affected tell their story.

Diwakar Rai in Kathmandu

At the beginning of 2025, Donald Trump signed an executive order which instituted a 30-day aid review, shaking the global development sector. With little warning, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) placed thousands of projects in 80 countries on hold and later announced a full suspension. This left millions of beneficiaries and development workers scrambling to save their projects and their jobs. The US government said that foreign aid no longer served the country’s national interest. Within days, grassroots development offices were closed, staff let go, and years of trust and reputation lost.

According to US government data, USAID managed $32 billion in 2024, enough to fund public health, disaster response, climate resilience, education, women’s empowerment, food security, democratic governance, human rights, media, and more. The largest chunk went as humanitarian aid to Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and Europe, and Ukraine. It is estimated that over 100,000 aid workers have lost their jobs, including doctors, engineers, educators, researchers, community health workers, and local NGO staff, many of whom had dedicated their lives to development.

My own country, Nepal, has long relied on foreign aid to support its economic and social development. Since the 1950s, the country has received generous foreign aid, with the United States as the largest donor, improving health, education and livelihoods. I’ve been working in development for over a decade. In 2023, I left a stable job at a South Korea-funded INGO to join DAI Global, LLC, which was implementing the USAID Biodiversity Project. It felt like my life had steered me in the right direction: helping to conserve my country’s rich biodiversity and getting paid very well. What more could I have asked for? But as the US election drew near, the buzz around Trump’s return grew. His climate denialism—calling climate change and everything related to it a “hoax” —made us feel hopeless, especially because our project focused on environmental conservation.

So, the election felt like an asteroid heading for our project, one which would either hit or miss. Eventually, we took the first and hardest hit, and our project was terminated. I was devastated. For weeks, I suffered from insomnia. I’d check my phone late at night and scroll through job sites. I spent my days in cafés, pretending to be busy while secretly looking for jobs. In Kathmandu, surviving without a job is tough; finding one with similar pay is nearly impossible. Around 2,000 development professionals in Nepal have lost their jobs since the funding cuts. According to the government, this number is still rising. Unemployment is high, competition is brutal: everyone’s scrambling for the same work.

Proma Parmita, Bangladesh

"Violence is quietly brewing in our cities"

I was a consultant for Encompass Inc.’s head office team, which monitors and evaluates (M&E) USAID projects in Bangladesh. During the last 12 years, I worked on multiple USAID-funded projects and was waiting for more to start when the U.S. government began cancelling projects around the world. I had carved out a stable, fulfilling career. Being a consultant on USAID-funded projects felt like the safest job. My expertise in M&E earned me the trust of many U.S. development companies, leading me from one contract to another. Short-term consultancies paid well over what the average salaried person in Bangladesh could earn in a year.

I could buy more time for my family as a consultant. Living in Dhaka is expensive, but with our combined earnings, my husband and I were able to live comfortably. We managed all the expenses, including supporting our parents and raising our daughter. But now, without new contracts coming in — although my husband never says it out loud — I can’t help but feel like I’m unintentionally burdening him with everything. But it’s not just me who is struggling; the consequences are far-reaching. Bangladesh has various socio-economic issues which USAID was helping to improve.

The USAID-funded Obirodh Project worked with NGOs and INGOs, encouraging religious and community leaders to preach tolerance and acceptance. The gender minority community, which is still called the “third gender” — socially unaccepted and looked down upon — remains cut off from the society of the so-called “first and second genders”. The USAID-funded Shomota Project rekindled their hopes and provided safe spaces where they learned hairdressing, tailoring and essential life skills to make a living. As a consultant, I’ve met these communities firsthand; I’ve seen how vital these projects are in giving them a sense of dignity, purpose and safety. But now, they are either struggling to continue or have already shut down due to funding shortages. This means violence is quietly brewing in our cities, and members of the third gender are once again on the lookout for hideouts, crippling their socio-economic and psychological progress. Their lives, like so many others, are becoming invisible again: uncounted, unheard and unprotected.

Karma Chandra Budha, Nepal

"My wife and I are expecting our second child this month"

I was born and raised in Karnali, Nepal’s most backward province. Due to the lack of roads, our world consisted of foot trails, suspension bridges and long walks to commute anywhere. Luckily, the government school I attended was supported by an NGO which provided books and stationery to poor students like me. I still remember the first bus ride I took to attend college in Nepalgunj City: I was so naïve that I sat in the driver’s seat and was laughed at.

With a bag full of hopes and dreams, I came to the city to find a job in development and help uplift the lives of rural people like myself while earning a decent income. It has been 15 years since I got my first job in an NGO. Since then, I have never worked in any other sector. When the government changed in the US, I had just joined Helen Keller International, which was implementing the USAID Integrated Nutrition, a project supporting thousands of pregnant women, lactating mothers and children under five, meeting their nutritional needs and reducing child mortality. But now, due to a funding freeze, life-saving nutrition services have stopped. In Karnali—already a food-insecure province—this has increased the risk of malnutrition and a rise in stunting, wasting and underweight cases among children.

Since I lost my job in February, it has become incredibly tough being the only breadwinner. My wife and I are expecting our second child this month and now I no longer have medical insurance. We already have a daughter to care for and pay a high rent in Kathmandu. I don’t know how many more months I can go on, or whether I should return to my village.

Bechara Samneh, Lebanon

"What if we get a desperate emergency call?"

I work for MENA Organisation for Services, Advocacy, Integration & Capacity Building (MOSAIC), an organisation run by and for the LGBTIQ+ community. In Lebanon, the infamous Article 534 of the Penal Code targets and penalises LGBTIQ+ individuals for “unnatural sexual activities” with up to one year in prison. Many have faced discrimination — physical abuse, death threats, assaults, rapes, gender-based violence — stripping them of their human rights. Syrian refugees who are also LGBTIQ+ face multi-layered violence. They have been attacked in broad daylight. The police are always on the hunt for them and they can be detained for up to a year in prison. They cannot report their cases or seek justice, which makes them more vulnerable. Many are in need of psychosocial support as they are left without access to mainstream services.

Supporting LGBTIQ+ is still socially unacceptable. Our office maintains low visibility, with no signboards and no Google location. Only our beneficiaries know of it, as it remains a target for extremists. If we have to relocate, landlords are unlikely to let to an LGBTIQ+ office. Despite all this, we were committed to running our projects. But things are getting tougher. This year, we managed to secure USAID funds, which would sustain us for the next three years. However, we were ordered to stop our new project in February. Now, we barely have enough funds to operate until May. More than the staff losing their jobs, I’m worried about having to stop all of the services for our 400 registered LGBTIQ+ individuals, including refugees from Palestine, Egypt, Iraq, Sudan, and Bangladesh. What if we get a desperate emergency call? Who will answer it and be responsible for their rescue?

Mohammad Alawadhi, Yemen

"My hands are bare."

Yemen remains politically and economically unstable. Since 2015, the conflict between the Sana’a-based de-facto authority (DFA) in the North, commonly known as the Houthis, and Yemen’s Internationally Recognised Government (IRG) in the South has led to a devastating humanitarian crisis. I have been working in development for various INGOs since 2012. The most recent was ZOA, a Dutch organisation active in Yemen since 2009, mainly working in food security, livelihood, and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). USAID was the largest donor for Yemen, providing 45% of the overall development funds. Through this, ZOA implemented projects for conflict-affected communities and internally displaced people (IDPs).

Due to conflicts, many main roads are filled with landmines. Communities become isolated, unable to fetch potable water; children cannot attend school; pregnant women do not receive timely health services and small-scale farmers cannot transport their produce to the markets. These projects were a lifeline, offering these people cash-for-work schemes to maintain mountain roads which served as safer alternative routes. Since I lost my job in January, finding another one has been a great challenge. I have attended several job interviews, but to no avail. Recruiters reply, “The job vacancy has been cancelled due to funding cuts.” Opportunities are hard to come by with so many INGO workers becoming jobless. Donor countries are changing their policies on foreign assistance and swiftly withdrawing funds from low-income and conflict-stricken countries. This has hit us all very hard. I’m a father of three children. My wife, parents, brother and some relatives all depend on me. But now, my hands are bare.

The Author

More articles of the Author