IRAQI KURDISTAN’S QUEST TO SAVE THE ELUSIVE PERSIAN LEOPARD

Following the rediscovery of Persian leopards in the mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan, local conservationists are engaged in a race against time to protect them from environmental dangers and the illegal wildlife trade.

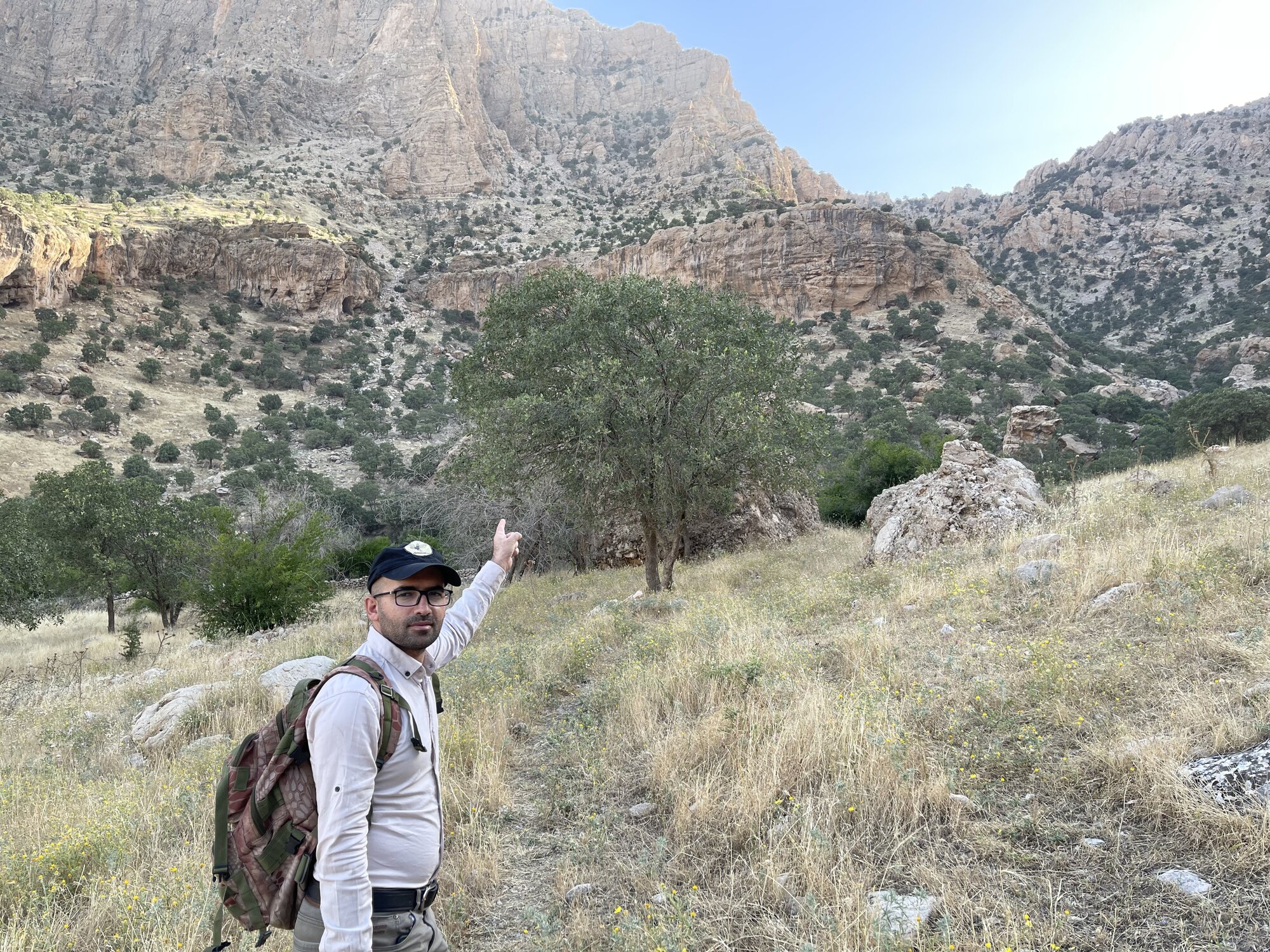

Soran Ahmed’s trip begins before sunrise. The winding road goes through a pass resembling a towering gateway framed by cliffs. On the other side, Ahmed must cross perilous ridges and giant crags that stretch up to form the impressive peak of Bamo Mountain, located southeast of the Iraqi Kurdistan Region. Ahmed makes his way to one of his camera traps that he has placed near a spring close to a village. His aim is to capture footage of a creature that, until recently, was long thought to be extinct in Iraq: the magnificent Persian leopard. The Persian leopard, also called the Anatolian or Caucasian leopard, is native to Iran and its surrounding regions. “The leopards were only rediscovered on the Iraq side of the border in 2008 when a villager found a carcass killed by a landmine on Bamo Mountain,” says Ahmed, a biologist and conversationist at the University of Sulaimani.

Strategically located within a buffer zone on the Iraq-Iran border, Bamo Mountain was a safe haven for the leopards in the past. “People kept away for fear of landmines and being shot by border guards, but the area has attracted more attention from hunters recently because of the leopard rediscovery and its wild goat population,” says Ahmed, shouting to be heard over the roar and honking of passing lorries transporting goods between Iraq and Iran. Experts estimate that a total of only 50 leopards remain in the Iraqi Kurdistan Region, scattered across different mountain ranges where they prey on wild goats, boars and other small mammals.

The need to protect the leopards is urgent, says Ahmed. Habitat destruction, drought and dwindling prey numbers due to hunting and poaching are the biggest risks facing the leopards. Local conservation efforts have been hampered by continuous conflict in the region and lack of official will to safeguard wildlife. Ahmed and his wife Soma, who is also a biologist, are among the few dedicated to this task. “Even the rediscovery of such a majestic creature has not motivated the government to introduce protective measures,” he says. Ahmed was a child when he first saw a leopard through binoculars in his birthplace Kanizhalla, a village located at the foothill of Bamo Mountain. At the time, he didn’t dare mention it to anyone. “I remembered when an old lady came crying to the village saying a leopard got one of her lambs and everybody laughed at her as though she was crazy,” recounts Ahmed who grew up scaling the mountain to herd sheep. The rediscovery of the leopards reignited his love for his village and region.

Documenting the numbers and location of the leopards is vital to their survival, especially because the beasts are increasingly encroaching on human territory. “Leopards only come near human settlements for water during the dry season. Sometimes, they encounter livestock and other domestic animals,” says Ahmed. “One of the leopards killed a cow belonging to my aunt in 2021. She was devastated since her livelihood depended on her livestock,” he recalls. “My relatives and other villagers wanted to use poisoned bait to kill the leopard but I vehemently opposed them,” says Ahmed. “People also do not understand the cultural importance of the leopards because, for a long time, they only survived in their memories,” he adds while checking his camera trap. Sadly, the camera has not recorded any footage of the elusive leopard this time.

The small cultural importance the animal currently enjoys is because of the efforts of activists like Ahmed. However, the lack of a unified, conservation programme and competition amongst activists for funding and resources have negatively impacted these efforts. Ahmed’s work was inspired by that of his biologist friend and mentor Korsh Ararat. Ararat was part of the first expedition to record the leopards through a camera trap in 2012 in the Qaradagh area near Sulaymaniyah. The project Ararat headed at the time was to survey the numbers and habitat of wild goats, which also populate the region along with herds of wild boar, both natural prey for the leopards.

On a scorching hot summer day in 2016, Ararat had a thrilling encounter with one of the leopards on Bamo Mountain. He was in the location to survey the area based on sightings by locals. “At first I thought it might be a wild boar. Then, standing 10 meters from me was the majestic leopard,” says Ararat. Shivers of excitement and fear ran through his body but he did not flee. “Seeing the animal in person was a very different feeling from seeing it in a zoo or looking at it through a camera lens,” Ararat recalls.

His second encounter was in 2020 when he and another environmental activist recovered the carcass of a young male leopard killed by hunters in the Piramagroon mountain in Sulaymaniyah. The sighting was reported by villagers. The carcass was entrusted to Ahmed who had it embalmed and keeps in his lab at the University of Sulaimani.

Ahmed and Ararat’s efforts have inspired dozens of other environmental activists and biologists to follow in their footsteps. To date, around 55 mammals have been identified in the IKR and only a handful of areas where Persian leopards roam have been studied through the personal efforts of people like Ahmed and Ararat. They hope to turn Bamo Mountain into a protected area, and say it is now a race against time due to the growing numbers of hunters and poachers that are often supported by powerful gangs trading in illegal wildlife.