Death at the border

Milica Švabić offers help and legal advice to refugees at Serbia’s border with Europe – but the dangers are great and many go missing.

A grey winter day in western Serbia. A cat is curled up on a broken suitcase in front of Loznica railway station. Next to it are two people huddled in sleeping bags.

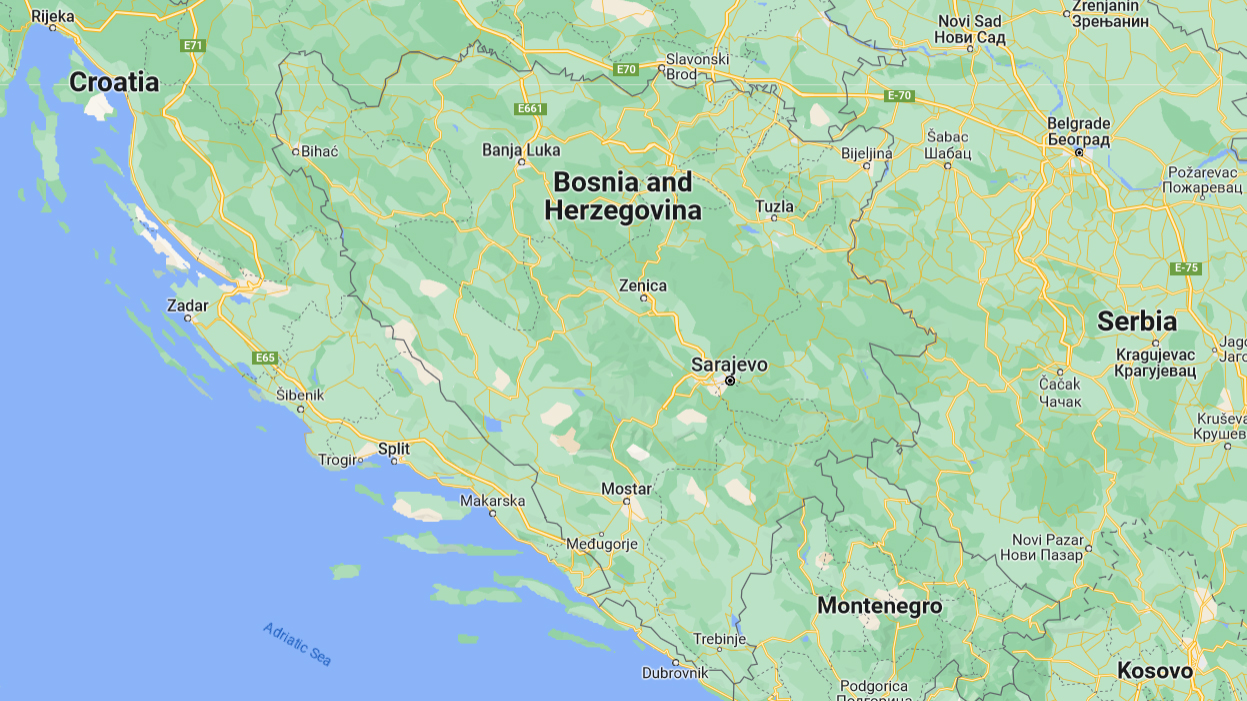

The small town of Loznica is close to the so-called Balkan route, which in the summer of 2015 was used by around 200,000 people from Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan, among others, to travel to the EU. Many still choose this route, despite all the dangers and harassment at the borders.

In the waiting room at the train station, Ali and his brother meet Milica Švabić, 34, a lawyer from Belgrade and a member of klikAktiv, a small but energetic Serbian organisation which provides help and advice to refugees in need. Along with her team of social workers and translators, Švabić documents cases of violence at the Serbian border and observes political developments such as the deployment of the European Border and Coast Guard agency, Frontex.

Their chief task, says Švabić, is to inform people in the area about their rights; equally important is to listen to them. That's why Švabić first lets the young man from Afghanistan tell her how he made his way this far and is now looking for a way to Western Europe via Bosnia and Herzegovina.

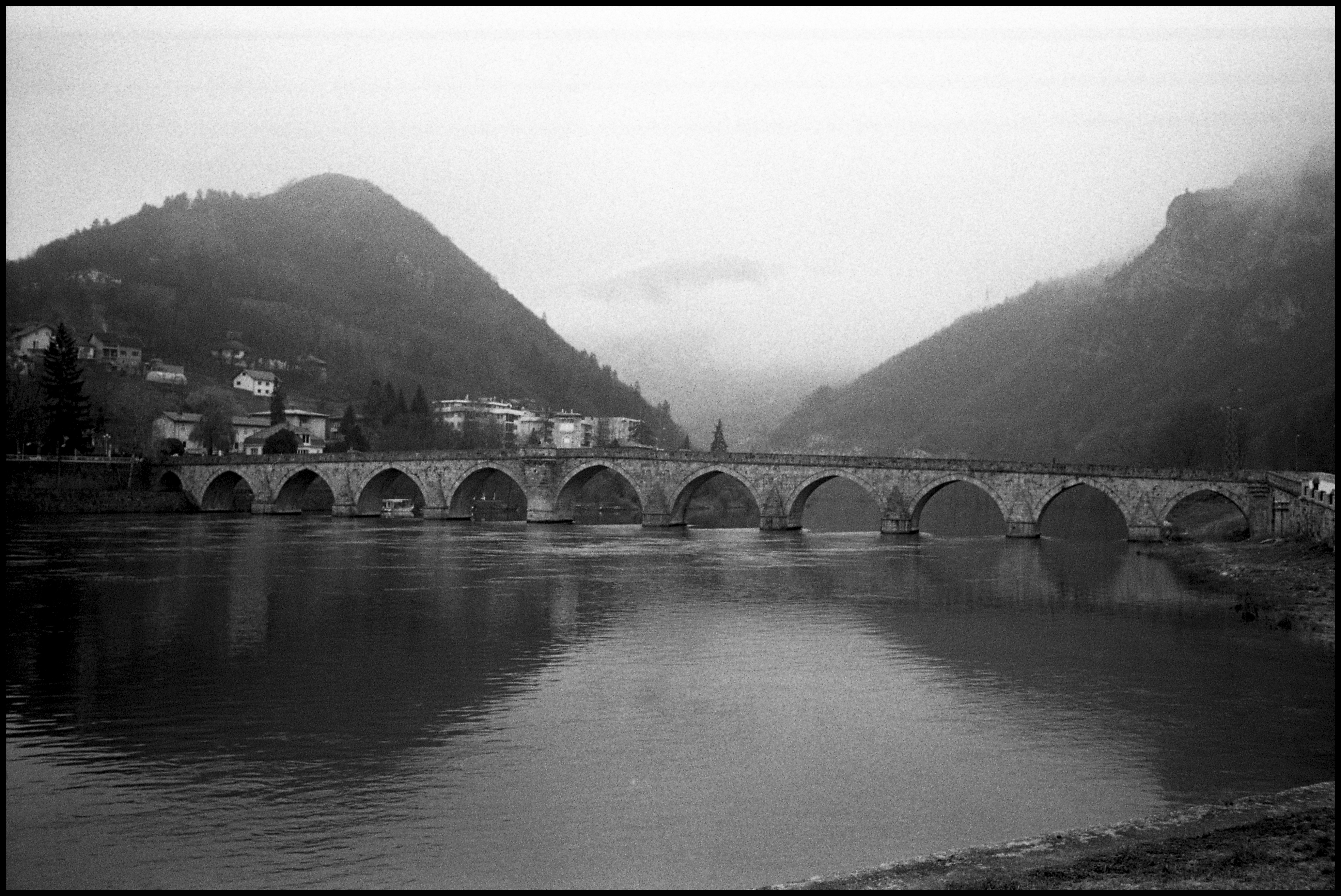

Their first attempt at crossing into the EU country failed after aggressive trafficking groups tried to force their services on them. They made it only as far as the border river Drina between Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Mehmed Paša Sokolović bridge, built by the 16th century Ottomans and immortalised by Ivo Andric’s Nobel-winning novel, "The Bridge Over the Drina", remains legendary and countless numbers have drowned beneath it in the strong currents. The scale and callousness of the Bosnian war was captured by the plea of the man who ran the hydroelectric plant below the bridge: that Bosnian bodies not be thrown into the river, because they would block the turbines.

It's unbelievable that we fled the war in Afghanistan and we have to flee from violence again!

Ali, Afghanistan refugee

Ali and his brother had shimmied to the Bosnian bank underneath the bridges. They made it, but the border police intercepted them and handed them over to the Serbian police. "The policemen beat my brother," says Ali, pointing to the young man sleeping next to him, his head on the table, his hood over his face. "It's unbelievable that we fled the war in Afghanistan and we have to flee from violence again!"

His greatest fear is that he and his brother might be sent back to the state camp in northern Serbia where they were registered before. Švabić reassures him that it is unlikely that the authorities will go to such lengths, but it is small consolation on the way into the unknown. In the end, she and the klikAktiv team can do no more than give the men warm jackets, soap and toothbrushes.

KlikAktiv at the border crossing

"I got into this accidentally," Švabić says. "I applied for a job at a human rights organisation in 2014 and was fascinated during the job interview. At that time, the topic of migration was not yet present in Serbia."

KlikAktiv was initially a volunteer project, although the team members have since been able to make a living from the work. Their funding, through private donations and small grants, remains uncertain, but provides enough to travel from Belgrade to one of Serbia’s borders every week. A common destination is Hungary, where hundreds of refugees hope to make it across the border and live in abandoned buildings or tents. “We distribute warm jackets, clothes and drinking water and provide free legal advice. People often ask questions about asylum procedures in the EU, but also if it is possible to have relatives join them.”

Irregular border crossing is very dangerous here. Hungary and Serbia are separated by a double-row fence up to six metres high, with NATO wire at the top and bottom. Anyone crossing risks deep cuts from razor-sharp blades, while Hungarian police also patrol between the fences. There are watchtowers, alarms that play through loudspeakers and even drones and thermal imaging devices.

Police violence

Those who are arrested by the Hungarian police are returned to Serbia, according to the refugees themselves. Such pushbacks are legal in Hungary and organisations including Human Rights Watch, Médecins Sans Frontières and the Border Violence Monitoring Network have documented that refugees are regularly beaten up and humiliated (klikAktiv also publishes reports on police violence). In a joint statement on 25 October 2022, eight of the organisations reported kicks and punches, and the use of rubber bullets and stun guns. In 2021 and 2022, Médecins Sans Frontières medical teams in the Serbian-Hungarian border region alone treated five hundred people who experienced violence at the hands of border guards.

People are too afraid to inform the police, even if it means leaving a dead person behind.

Milica Švabić

During the winter months, the situation in northern Serbia worsened too, with Serbian police cracking down on people staying outside the official camps and destroying informal settlements near the border. Serbia borders on eight neighbouring countries and thus has a central position like no other country in the Balkans. The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) reports that nearly 300 people have died or disappeared along the Balkan route since 2014."The number is certainly much higher," says Švabić, "but most cases are neither reported nor registered because people are too afraid to inform the police, even if it means leaving a dead person behind."

A group of young men from Afghanistan and Pakistan told her two years ago that they had gone in search of two friends who had disappeared while trying to cross the Drina River. They informed Švabić, gave names, photos and exact descriptions of their friends. She informed the police and the local hospital in Loznica. "I got no answer, neither from the police nor from the hospital," she says. Friends of those missing then started their own search. They discovered nine other deaths: some of the bodies were found on the riverbank, others they learned of from local residents.

From the bureaucratic hurdles Švabić encountered trying to identify the dead, so that they could be returned to relatives in Afghanistan and Pakistan, she realised that those who die at the borders often disappear into anonymous graves. Their families never know what happened to them.

Calling prisons, cemeteries and hospitals in search of missing or dead people is not part of klikAktiv's mission, but Švabić is contacted again and again when desperate relatives or friends are looking for missing people. In the case of the group of young men from Afghanistan and Pakistan, the repatriation of their bodies was ultimately successful, but only with the help of a private funeral home which facilitated the identification and transport. Švabić suspects that dead people who are assumed to be refugees because of their skin colour and appearance are not even brought to the hospital. "Instead," she says, "the bodies are taken to the cemetery and buried." Officially, an autopsy should be performed and a DNA sample taken to clarify the cause of death and enable later identification. But small hospitals usually don't have a doctor who can perform an autopsy and having experts travel from Belgrade is expensive.

Anonymous graves

"When they see in the hospital that it's a migrant, they don't want to pay," says Švabić. "As soon as a person is buried, that's it." Plus, the identification of a body in Serbia can only be recorded by a family member, but in these cases most relatives would not be able to make the trip. "How is that supposed to work? The time between finding the body and burial is very short." Instead, graves in small cemeteries near the border are marked with just a number or the inscription "Unknown person".

Brutality of border deaths

A village about six kilometres from Loznica on the Serbian side of the Drina. In the abandoned railway station with its broken windows and crumbling walls, people seek shelter before crossing the river - or after being forced to return. Leftover food, empty energy drinks and ashes from a fire in the middle of the draughty room are the only signs that people have been here. Now the ruin is empty.

Outside, Švabić chats with an old man who is loading branches into his wheelbarrow. He reports that fugitives do seek shelter here at night, but when the police show up, as they did today, they hide. He makes a gesture towards the railway tracks behind which the border river runs.

As Švabić climbs through the ruined railway station, she remembers a group she met here in the summer of 2020. "We met them a day after their failed attempt to cross the Drina. They told us how policemen on the Bosnian side laughed loudly when one of the men was about to drown. They saw him drowning and didn’t do anything. The man drowned."

This is not an isolated case. People are also dying along the railway tracks in Serbia and North Macedonia. In overcrowded cars, smugglers try to transport refugees through Hungary to Austria. When the police take up pursuit, there are daring chases which sometimes end in fatal accidents. Rarely do border deaths receive wider media coverage, as they did on 17 February 2023 when eighteen people from Afghanistan were found dead in a truck in Bulgaria.

There is no humanitarian corridor for refugees, no way to reach Europe safely.

Milica Švabić

"All this happens because there is no humanitarian corridor for refugees, no way to reach Europe safely," Milica Švabić says, "so unfortunately there are more defeats than successes in my work. But the small victories are what motivate me to keep going."

One of her reports helped avert a deportation from the Netherlands to Romania last winter, a victory, because in Romania refugees risk being deported to Serbia on the basis of a bilateral agreement between the countries. This is in spite of the Dublin Regulation that a refugee must apply for asylum in the state where he or she first entered the EU.

Švabić does not know what has become of Ali and his brother. She usually only meets such people once. Maybe they made it across the Drina after all. Or even into the EU.