Dangerous Relations

In parts of Azerbaijan, marriage between relatives is a cultural norm, leading to dangerous levels of hereditary disease. Ismayil Fataliyev reports.

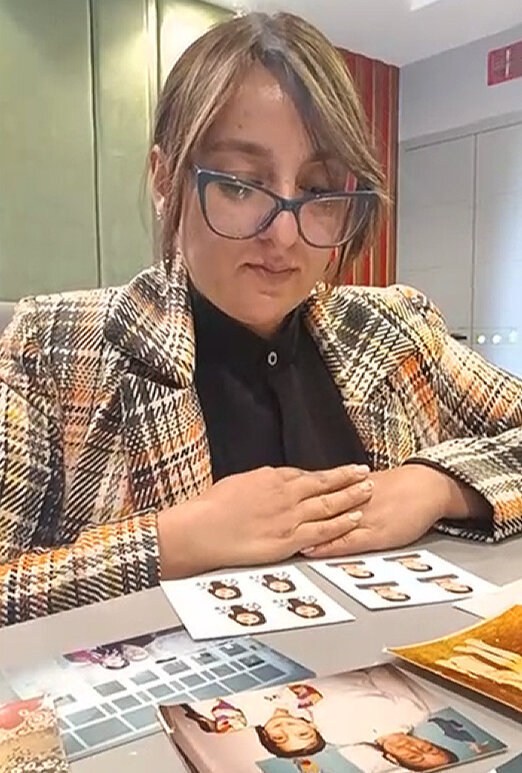

When she became an orphan, Nubar Azizova was raised by her great-aunt. When she grew up, she fell in love with a man she wanted to marry, but instead the great-aunt wedded her to her son. Solmaz is Nubar’s daughter. “My parents had an opposite worldview," she said. "Elders destroyed Nubar’s life.” Solmaz is 41 and, until 2015, she had a sister, Jamila, who was two years younger than her. Jamila had thalassemia, a hereditary disease which affects the blood.

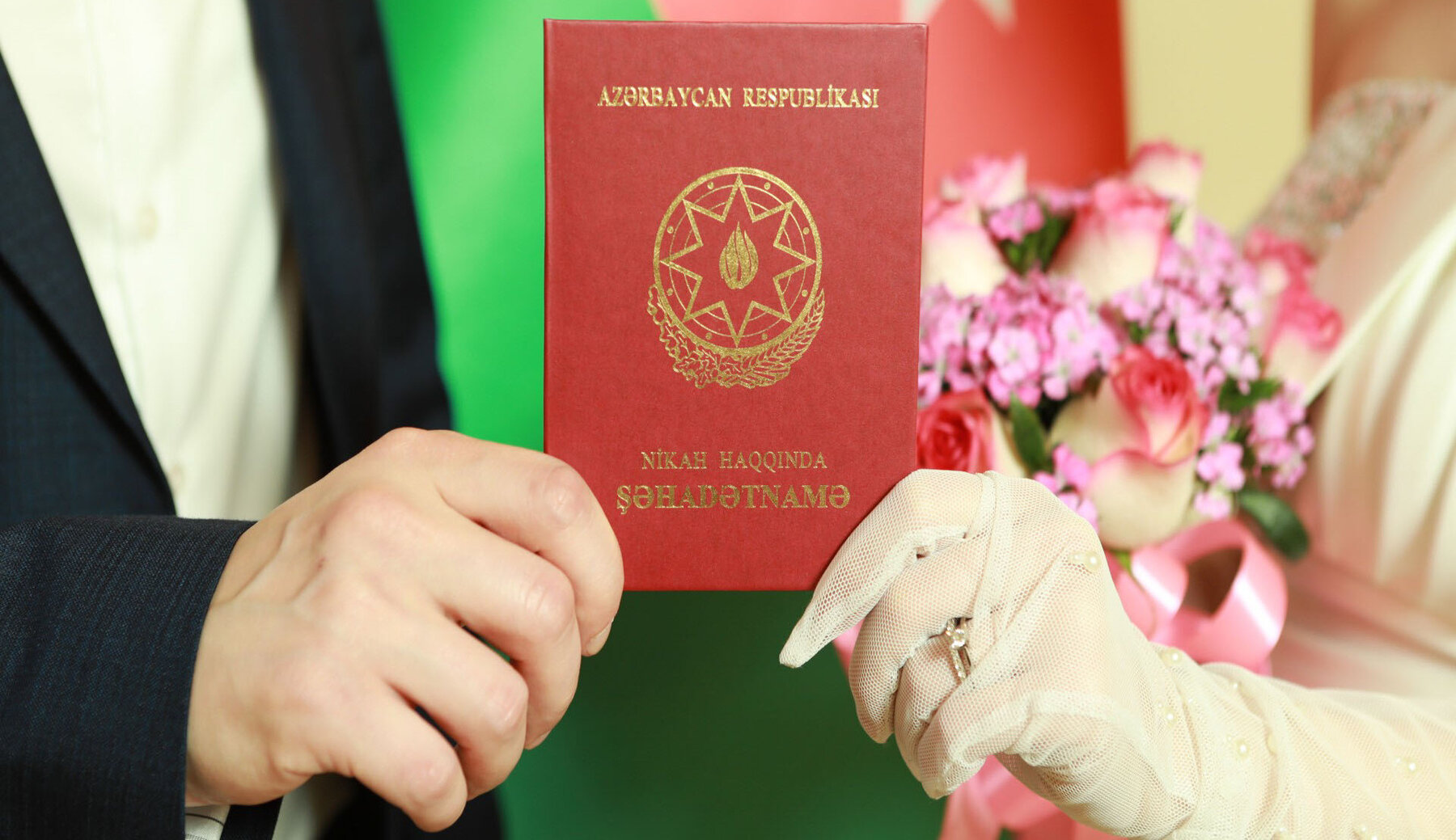

“Jamila lost weight and had abdominal pain,” said Solmaz, who is a hotel receptionist in Goychay, Azerbaijan. “Her skin got darker. Her legs and body began to swell.” To help her, Jamila’s relatives - and later a public thalassemia centre - donated blood for 17 years.But eventually, she died. Solmaz blames the consanguineous marriage. “Parents look for chaste brides among relatives whom they trust,” she says. In Azerbaijan, the cultural phenomenon of consanguineous marriages has increased cases of genetic diseases, with thalassemia the most widespread. In 2023, there were 4,916 cases of thalassemia reported, 820 more than in 2022. There have been moves to address the problem. Since 2015, couples must take a blood test to find out if they have thalassemia, AIDS or syphilis. Since 2020, the registry office has obliged newlyweds to specify their kinship. In 2022, the number of consanguineous marriages reached 2,542, around four per cent of all registered marriages.

But now the government has banned such marriages. Azerbaijan’s Family Code now prohibits marriages among parents and children, grandparents and grandchildren, siblings and children with a shared parent, adopters and adoptees, those who refuse to take medical tests, and those with mental disorders. Sceptics say the new law will mean couples will not seek to register, instead opting for so-called kabin, a religious marriage which is not recognised by the secular government, but is venerated by its society. “Courts won't be able to settle any family dispute arising out of the unregistered marriage,” says Azerbaijan’s state committee for family, women and children’s affairs.

The effects of consanguineous marriage have had a profound effect on this country of 10 million people. Every 50th person carries the thalassaemia gene. “As they are recessive or hidden genes, they manifest themselves sooner or later,” says Zakir Bairamov, a Baku-based medical geneticist. The worldwide average ratio of haemophilia, another genetic disease, cases is one thousand per 10 million. In Azerbaijan, it is over 1,700.

Said, who is 17, has infantile cerebral palsy, a partially genetic disease. He is unable to move, eat or drink by himself. His mother, Aynur, a 42-year-old jewellery seller from Baku, did not want to marry the cousin who visited them as a student. But since she did not meet a soulmate among her non-relatives, she agreed. Fortunately, Aynur also has two daughters of 9 and 13, who are unaffected. Although a relic, the attraction of consanguineous marriages remains strong in Azerbaijan. “A stranger can demand an expensive dowry,” says Sanubar Heydarova, a sociologist. “To avoid this, rich families preferred a family member both then and now.” Poor families also follow the tradition, cleaving to a rule that “a relative is aware of what we own and won't ask for more.” Azerbaijan’s strong regional and tribal identities are also to blame for the situation. While families in some regions are flexible, in places like Masalli, in southern Azerbaijan, families don't want a stranger as an in-law. “They seem to follow a tacit rule: marry relatives or fellow villagers,” Aynur says, citing stories of female colleagues from Masalli.

One of the most popular wedding songs is “Cousins are made for one another”. There is a proverb which says, “Eat your relative’s flesh but never throw away his bones,” meaning when two relatives are at odds, they still stick to each other. Heydarova, the sociologist, says some parents ban their children, especially girls, from making male friends outside the family. “These children don't have other age-mates in their lives except for cousins. The less often cousins meet, the more likely they are to fall in love and marry,” she says.

Knowing a relative is a "pure girl" or “decent boy” still seems to outweigh the risks of genetic disease and a child's happiness. “It is a kind of lottery whether you are lucky or not,” concludes Aynur. “If a relative proposes to my daughter, I will refuse. Whenever someone around me supports this, I urge them to look at my situation.”